Thomas Samuel Williamson, JR

From The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit, Oral History Project interviewing Thomas Williamson:

(For the whole oral history you can read it here)

Mr. Williamson:

We moved into Piedmont in 1952. Before then we lived in East Oakland. East Oakland now is all black, although at the time that we were there, it was a more racially mixed community. Piedmont was right next to Oakland. It was a much more affluent community. The range in Piedmont was pretty much solid middle, to very, very rich. It didn’t really have poor people in Piedmont, and didn’t really have very many working class, blue-collar people. My father was an army officer, so we were not wealthy, and we did not live in the sort of mansions that many of my classmates did. But, we had a perfectly nice four bedroom house.

So there were many challenges for my mother in terms of just, you know, how do you get groceries when you have three kids? So as a child growing up, I had a big basket on my bicycle. I would often be sent to the grocery store to get stuff. We all had to learn how to use public transportation, which some people think nobody in California during the 1950’s knew how to use the buses, but my mother certainly did. She said, “You don’t have to wait for the bus for long if you know what the schedule is. You just are there a few minutes ahead of time.” And, I am trying to remember how she used to get out to the place where she could buy groceries most inexpensively at the base Commissary. And right now, I have to go back and ask her how— when she wanted to really go buy a lot of groceries—how did she get back and forth to the Commissary. Because the buses that we took from Piedmont—we had to take three different buses to get out to the base. When we were a little younger, we had lived on the base. And that’s when my dad was, I think, before he went to Korea. Then we moved to East Oakland. Again, I think before he went to Korea, and lived there for a while. And then he went to Korea. And then, when he came back, we moved to Piedmont, which is where my mother still lives.

Ms. Boone:

Same house?

Mr. Williamson:

Same house that we grew up in. But she, well both of them, I think, are part of the greatest generation that doesn’t really get the notoriety and attention that has been focused on Caucasian members of the greatest generation. And I think it’s because we haven’t really had, I don’t know, a good book or a good movie about what an extraordinary challenge it was for black parents to be raising children in an America that was in the midst of beginning to integrate. In the 1950’s, especially in the South, but also in many northern cities, if you didn’t understand the written and unwritten racial laws, it could be very dangerous for you. I don’t know if you knew, in the 1960’s, there was a black kid who was looking for a summer job in Cicero Chicago. And he was killed just because he came up to somebody’s door and asked for a summer job. I think it was-- Cicero was a Polish neighborhood in Chicago.

...The reason, in Piedmont, that we had got our house, actually, was that the former owner was a very interesting white guy, sort of iconoclastic white guy, Mr. Stotten, Rio Stotten. He didn’t like Piedmont, which was very conservative. It was a very conservative community back in those days. Very conservative. Primarily Republican community. He didn’t really like the environment there. So, I think in part, one of the ways he decided he’d get back at Piedmont would be to sell the house to a black family. (Laughter) So he fixed Piedmont with the Williamsons. (Laughter)

...But my parents adopted an approach that—I think there were a number of African-American parents who were, who would move their families into integrated situations and concluded or believed that—if you started talking about race it will encourage your children to feel hatred toward white people. Particularly if you told your children the truth about how racist America was. So, they did not bring us up with explicit racial consciousness. They brought us up with the view that, “You are as good as anybody in this community.” That’s the basic value. And “We want you to take advantage of the schools, the recreational programs, to the fullest extent.” And “Do your best.” Now they didn’t say it in so many words, when they said, “Do your best,” you just realized even as a black child, that really meant that you had to do better than all the white people.

In retrospect, I had this awareness that would play out in ways that, in retrospect, were unfortunate to have to deal with as a child. But, they are ways that shaped me a lot. For example, understanding that somehow, whatever I did, particularly if it was bad or deficient, would be attributed to all black people. Nobody said that in so many words, but you got that fairly early. When you outdid white people, they didn’t attribute that to all black people. Then they shifted to, “Oh, you’re an exception.”

...Some kids never invited me over to their house, even though that was very normal for children in my community. My brother had an experience—I didn’t run into this directly—where he was invited to someone’s house, and when he got to their doorstep or their porch, the mother of George’s friend said, “Well, you can’t come in here. We don’t, you know, allow anyone black in our house.” You know when you’re a little kid that’s pretty crushing and bewildering. It’s like, “I didn’t steal anything from you and I didn’t beat up your kid. Why would you feel that I can’t come into your house?”

On the other hand there were families that were very welcoming and warm. So that, I think it really didn’t make sense for me to develop a stereotypical view of white people. I knew a whole lot of white people. I knew how different they were, both toward me and toward each other. For some things I didn’t pick up on until later were just ironic, -- just remember it’s a small town. Piedmont is only twelve thousand people. It had three elementary schools, one junior high and one high school. This is really small town America. Twelve thousand people. In my elementary school, there was just one class of 25 kids. So that means in your grade you have twelve or thirteen boys and twelve or thirteen girls. That’s small. But that also meant you were aware of what happened to everybody. So when we were old enough to be Cub Scouts, all the boys wanted to be in the Cub Scouts den. But Jerry Goldstein for some reason didn’t become a Cub Scout. And it wasn’t until a couple years later I learned that the Den Mother, I think it was Donald Graham’s mother, he was a kind of pudgy, blond white kid, she was anti-Semitic and ironically, apparently did not object to a black kid being in the Den, but she would not let a Jewish kid join. Again when you’re in a little, small school and everybody knows each other and what you’re doing, you’re very conscious then of being left out of what the other boys are doing, because there is literally ten or twelve boys in the class.

So we were embraced by the teachers in the school system. You know how sometimes you run into these teachers who-- they don’t seem to like children and you’re wondering, “Like, why are you a teacher?” The third grade teacher seemed like that to me. But particularly my second grade teacher, my fourth grade teacher, my fifth grade teacher—they didn’t seem to like kids too much either— and my sixth grade teacher she just loved the Williamson kids.

In our little town, our neighborhood, your social life, if you will, for the boys revolved around being at the playground and that was when, in those days, you would have a college kid who was hired by the recreation department—or two of them, usually a guy and a girl—to be playground directors. They would help to organize activities. They would just watch over the kids to be sure nobody did anything really stupid. And if you got hurt they would take care of you. To a person, all of the playground directors were very supportive of me and my brother and my sister. The girls didn’t come down to the playground as much, but my brother and I pretty much lived there. To the point where if anything, there was kind of discrimination in favor of us in some instances. For example, once somebody stole twenty dollars from the purse of the female playground director. The police were called to the playground and they interviewed all of the kids who had been on the playground, except me because the director Joe Maroux had said, “There’s no way he did it.” So that was very different than the experience of black kids around America.

...But, again, there were dimensions of the experience that were really quite positive and welcoming. But in some ways they were not the greatest training for getting ready to understand what was out there in the larger American society and understanding how most black people oriented to what was going on out there and understanding how most white people thought about you. So third grade, Brown v. Board of Education, would have been too early and also it didn’t result in any change in my situation. I had started in kindergarten in 1952. I think it was 1951. I think it was 1951 or ’52. But, for me, I showed up at school and knew the kids from being on the playground. And it didn’t really occur to me until maybe the fifth grade when there was this white kid who was maybe a couple years older who said, “They’re not gonna let you go to the high school.” I, by then, knew the civil rights movement was going on and there were these school desegregation issues. So everybody knew in ’57 there was an enormous amount of publicity around what happened in Little Rock at Central High. I don’t remember if I asked somebody or my parents about that remark. I didn’t like the guy who said it to me. And I didn’t trust him in other ways. And there was nothing else signaling that I wouldn’t be going to the junior high or the high school and there were things suggesting that some people were looking forward to my coming there. It was a small town, but if you were a good athlete, everybody knew about that, too. We played -- there were three elementary schools -- we, you know, we had a little league where we’d play against them. Other than this one guy, John Batalie, no one ever said anything like that and that was not an issue. But, I was becoming increasing aware that there were parts of the country where there were these—what seemed to me even as a little kid—these kind of savage, insane reactions to black kids coming to the same school as white kids. When you’re a little kid, it’s pretty difficult to understand why that would be a source of controversy and violence. You just wanna come to school.

Now, at that time, I wanted to be like everybody else. I wished I had freckles and straight hair. I asked my mother if I could straighten my hair. Back then there were black entertainers and a lot of political figures, a lot of ministers, they would conk their hair. My mother said absolutely not. She said, “Are you crazy?” So I got the signal that was not cool. But, most kids, I think, want to be like their peers. And that was the world I lived in. I was coming to the realization I couldn’t be like everybody else and I had to start figuring out how to deal with being, you know, the only “Negro” in my class. Until I got to high school, we were the only black family in the community. The only other black kids in the school systems were my brother and sister for a while. There was one of my aunts, her children lived around the corner from us, but they moved out when I was in high school. We were the only black people.

But at the same time, for example, when I finished with the Cub Scouts I joined the Boy Scouts, and by chance, the troop that I joined was run by a school teacher who was very resourceful and creative about the programs that he established. We had the largest troop in Piedmont. Most troops had 20-30, we had 100 kids in our 26 troop. It was really big. He seemed to recognized positive qualities in me very early. Even though I couldn’t swim, and in order to become, I think it was, a first class scout eligible to be a patrol leader, you had to have the swimming merit badge or something, he granted me a waiver because he wanted me to become a patrol leader. And it was also pretty clear to me that he wanted me to become the senior patrol leader, so that I was in charge of Sting Ray Patrol-- I was the scout, the highest ranking scout in the troop. And he was very good about teaching leadership skills. He would prepare an agenda, and we would consult about what would be on the agenda. To me, it seemed natural, because, by then, around the time I got started in scouts, Boy Scouts, my father had been able to arrange to get himself stationed back in the Bay Area. Being who my dad was, he wanted to make up for this time away. A lot of these scouting things—camping trips and whatnot, but mainly camping trips—you know, they asked dads to come along, but only a few come. My father never missed a camping trip. Plus he was an Army officer and so when he learned, you know-- he was a country boy and an Army officer, so camping was just second nature to him. He was a Lieutenant Colonel by then. So, people would refer to my father as just the Colonel.

...I’m not sure if there was an election. I think the scout master decided who would be the senior patrol leader. But that was-- since my patrol had outdone the other patrols that wasn’t-- I don’t think that was a controversial issue in the community that I was operating in.

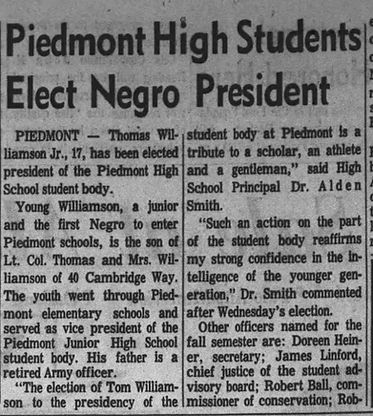

I think the first incident that really brought home just how strange and racist the society was, was when I was in the eighth grade. I ran for vice-president of the junior high school and was elected. You know, being a Williamson child, I didn’t think it was that big of a deal to be the vice-president, since I wasn’t the president. But I am not sure why I decided-- I probably figured there was some other kids that were more popular, so I’d have a better chance running for vice president. But to my astonishment, my election to be the vice president of Piedmont Junior High School became a front page story of the San Francisco-- in the San Francisco Chronicle, which was the biggest paper in San Francisco then. It was covered by the radio stations.

...I think it’s pretty weird. I’m just the vice-president of the junior high school. But it’s clear this seemed quite remarkable to white America. And you also have to understand that Piedmont was known to be this very socially elite community. You have San Francisco society on one side of the Bay and then on the East Bay Side—Oakland, Berkeley, Piedmont—Piedmont was the place where there were debutants and coming out stuff. A lot of wealthy people. So yeah, front page of the Chronicle. On the radio stations. Probably would have been on the TV stations, but my parents wouldn’t, they wouldn’t allow me to be videotaped or photographed. And I came to understand fairly quickly why. Because after this publicity, we started to receive hate mail.

The San Francisco Examiner -

Fri. Oct. 9, 1959

The Sacramento Bee - Fri - Oct. 9, 1959

Oakland Tribune - Fri - Oct. 9, 1959

...We started to receive threats on my life, which, you know, again, when you’re thirteen, this is a very strange country. Why are there people that feel threatened that there’s some thirteen year-old black kid who’s the vice-president of the junior high school—an all-white junior high school. But it was sobering. In a way that helped me connect and understand these things that are going on in the South could happen here. In fact, I used to always have to walk to school, but for two weeks after these articles came out, my father drove me to school because they were concerned that something might happen.

...I very naively thought that if I set a positive example, white people in general would understand that you shouldn’t stereotype black people as a group, that you should appreciate that there are black people that have the same or greater abilities as you do, and that the society should be interested in supporting and nurturing black people just as white people are nurtured, so that the best and the brightest could contribute to society.

Ms. Boone:

But instead you were seen as an exception?

Mr. Williamson:

Yeah. I mean that was underscored when I graduated from high school. Graduation night when I was the, I gave the-- I wasn’t really the valedictorian. I didn’t have the highest grades. I may have actually been fifth in my class. But at my high school, they didn’t do it just on grades. They picked the student who was considered the outstanding student-- who was deemed to be the outstanding student, and you gave the speech at graduation. And classmate after classmate came up to me and said, “Tom, it’s really been great being in high school with you. You know I really don’t even think of you as being black anymore.” And so, I knew I was going far away for college and this reaffirmed why I wanted to, or why this community wasn’t fulfilling to me and it of course frustrated and depressed me to think that the model Negro approach was largely ineffective. These people didn’t generalize to the rest of the black community what they thought about my positive attributes or qualities that they regarded as superior to theirs. They moved that into the exception category, as if somehow I didn’t belong to my own race because I was so much better than they were.

...My parents wanted us to be fully integrated into Piedmont. So even though my father was of the Baptist tradition, he wanted us to be at Piedmont Community Church. I went to the church-- You know I had a funny incident that in retrospect, may have been a little bit of discrimination. I was eight or nine years old. I think I went up by myself, because again, my mother, she didn’t have a car and they wanted me to go the church and I asked how I could join. They said, “Well, you have to memorize the 23rd Psalm and the 100th Psalm in a week in order to qualify to be at church.” I have a feeling if I had been a white kid, they wouldn’t have asked me to do that. But it didn’t faze me, since to me that was just another student task, and “Oh I can do that.” So I just memorized the psalms, came back and recited them, and, “Okay, you can come here.”

...If you were a white kid and you started to date a girl from Oakland High, Piedmont kids would kind of suggest, “Why would you be going out with such a low class person.” So in other words, very few events were-- social events, where kids from any other school came to Piedmont, were so parochial.

...I wrote an essay about a game that used to be played, which I was afraid to think about in a focused way, when I was growing up in Piedmont where somebody would say, they’d point to the fence on the other side of the playground and they’d say, “Last one to the fence is a nigger baby.” I was the fastest kid on the playground, so I was always the first one to the fence, but what I wrote about was the realization that I was still the nigger baby. So I think in my own mind, I was saying the way the white world has tried to shape my values and my sense of self-worth was not going to work for me. I need to come up with my own way of doing that. I realized that there was something instinctive about saying, you know, these people or this society doesn’t really value your heritage and your ancestry. And so you can’t count on white America to both introduce you and encourage you to appreciate that heritage. So even though I was this black kid who had grown up in a very conservative white community, I said I need to begin a journey to find out who I am on my terms, rather than their terms.

Oakland Tribune - Thu - Dec. 12 - 1963

Oakland Tribune - Thu - May 30, 1963

Oakland Tribune - Wed - July 24, 1963

Oakland Tribune - Thu - Jun. 4, 1964

Oakland Tribune - Mom - Dec. 18, 1967

From The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit:

THOMAS S. WILLAMSON, JR

Thomas S. Williamson, Jr. was born on July 14, 1946 in Plainfield, New Jersey. His parents, Mrs. Winifred Hall Williamson and the late United States Army Lieutenant Colonel Thomas S. Williamson, Sr. -- one of the first black officers to command white troops in the U.S. military-- were later stationed in Yokohama, Japan where young Tom reportedly spoke Japanese before he spoke English. The family ultimately settled just east of the San Francisco Bay in Piedmont, California where Tom grew up with his two younger siblings -- his late brother George and his sister Brenda. They integrated Piedmont and experienced the vicissitudes it brought with the mix of well-meaning and less well-meaning neighbors, classmates and teachers.

Tom's parents instilled in their children the importance of education and doing their best in all they did. It paid off. His work ethic earned him letters in track, basketball and football, and an MVP trophy, and led him to become his high school student body president. Moreover, Stanford University's assistant coach Bill Walsh, who later became Stanford's head coach and a triumphant NFL head coach, relentlessly recruited Torn given his prowess on his high school gridiron. Despite Stanford's full athletic scholarship offer, Tom chose to accept Harvard's academic scholarship to enable him to experience the full range of student life. His student life in the wake of Dr. King's assassination included chairing a black student committee that successfully negotiated with Harvard's administration to broaden opportunities for enrolling African American students and to establish a department of African American studies. Tom also lived the grueling life of a gifted allIvy League defensive back, All New England and All East (second team) on Harvard's football tearµ. He received the Allston Burr Prize for the outstanding scholar athlete, graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1968 and was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. His academic and leadership achievements earned him a Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford University. He later spent a year in Ethiopia training U.S. Peace Coips volunteers for an Ethiopian company. But it was largely Tom's summer experience before his senior year at Harvard as an advocate at the California Rural Legal Assistance program on behalf of poor people and migrant workers that propelled him to become a lawyer.

Tom enrolled in law school at Boalt Hall at the University of California, Berkeley in 1971 where he later became a Notes & Comments Editor of the California Law Review. In his first year, he joined fellow students in protest over the school's decision to cut back on diversity admissions and went on a strike that shut down the law school for two weeks. He later spent time working as an extern in a public interest law firm called Public Advocates. Enticed by Covington & Burling's program that permitted young associates to be on loan to the Neighborhood Legal Services Program for a six-month rotation, he accepted Covington's offer to join the firm and moved to Washington, D.C in 1974 after graduation.

Government service lured Tom from Covington twice. In 1978, he was appointed as the Deputy Inspector General of the newly established United States Department of Energy in the Carter Administration. Soon after returning to the firm in 1981, Tom became its second black partner. He left the firm again in 1993 when President Clinton nominated Tom, and the Senate confirmed him, to be the Solicitor of Labor in Secretary Robert Reich's Labor Department.

What followed his return to Covington in 1996 was a continuing extraordinarily accomplished and celebrated career. Within the firm, he led the employment practice group and was a member of the management committee. Tom also led a team of Covington litigators before the federal trial and appellate courts out west defending a constitutional challenge to various restrictive regulations that had been adopted by the Legal Services Corporation (lSQ. The leadership of LSC credited Covington's defense of the regulations with sparing LSC from a total cutoff of Congressional funding. Tom chaired the court-appointed Texaco Task Force on Equality and Fairness that monitored and evaluated Texaco's nationwide efforts to reform and enhance diversity initiatives and equal opportunity. He was retained by the National Football League as special advisor to the Owners' Workplace Diversity Committee and the General Managers' Working Group established to facilitate increased diversity in the head coaching and front office ranks of NFL clubs. He played a key role in developing the NFL's "Rooney Rule," designed to promote increased opportunities for minorities to become head coaches in the NFL More recently, Tom co-led a team that assisted in the defense of the District of Columbia's same sex marriage law. He also worked on race and disability discrimination class actions, including a nationwide class action to obtain dramatic improvements in American Sign Language interpreter services for thousands of deaf employees of the U.S. Postal Service and $3.5 million in compensatory damages. He chaired the monitors implementing the Sodexo class action race discrimination consent decree.

Tom served our community in countless capacities. His contributions to the D.C Bar included chairing the Family Law Task Force, and serving as a member of the Board of Governors, the Bar Foundation, and the Pro Bono Committee. He was elected President of the D.C Bar, and pursued as his priorities supporting legal services for those who cannot afford them and strengthening relationships with the local courts. He was appointed to the D.C Access to Justice Commission, the Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs (Co-Chair; Trustee), the D.C Judicial Nomination Commission, the D.C Commission on Judicial Disabilities and Tenure, D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton's Federal Law Enforcement Nomination Commission, and the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law (Trustee). He served his alma mater as a member and the President of the Harvard University Board of Overseers, and as a director of the Harvard Alumni Association. He was recognized as one of "The 50 Most Influential Minority Lawyers in America" by the National Law Journal, and was featured in Washington DC Super Lawyers - Employment & Labor, and Best Lawyers in America, Employment Law - Management.

Tom's numerous accolades and awards included the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Segal Tweed Founder's Award, the D.C. Legal Aid Society Servant of Justice Award, the Council for Court Excellence Justice Potter Stewart Award, the District of Columbia Law Students in Court Celebration of Service Award, and the Washington Lawyers' Committee Wiley Branton Award. Conversant in French, a fan of classic Motown R&B, and a member of Epsilon Boule of the Sigma Pi Phi fraternity, Tom enjoyed travelling, was an avid Lawyers Touch Football League player into his mid-30s, and later was a committed cyclist completing several 100-mile bicycle rides. He is survived by his devoted wife of 28 years, Shelley Brazier; sons Thomas III (Tommy) and Christopher and daughters Taylor and Kai; mother Winifred Williamson; sister Dr. Brenda Malone; brother-in-law Sherman Malone; sisters-in-law Sylvia Williamson and Benita Brazier; nephew Tony Williamson and niece Audrey Williamson; and a host of relatives, colleagues, and friends. We will miss him deeply, but his memory shines brightly inspiring us to do more for others in need.

East Bay Times Newspaper, 3/28/2017

Piedmont: Thomas Williamson’s remarkable life, career recalled

PIEDMONT — Rhodes Scholar and former Piedmont resident Thomas Williamson enjoyed a remarkable life and legal career whose resume included work with the United States departments of Energy and Labor, defense of a District of Columbia same-sex marriage law and a role in a class-action lawsuit requiring better American Sign Language interpreter services for deaf U.S. Postal Service employees.

A longtime partner and later senior counsel of the prestigious Covington and Burling law firm, Williamson also helped the National Football League establish its “Rooney Rule” to include minorities for consideration of head coaching jobs. A 1964 graduate of Piedmont High School who advanced to Harvard University and ultimately graduated from Cal’s Boalt Hall School of Law in 1974, Williamson died Feb. 24 in his Washington, D.C., home. Williamson, who suffered from pancreatic cancer, was 70.

“Tom was a dear friend, trusted colleague, and distinguished public servant,” former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich said via email through Cal’s Goldman School, where he currently serves as a professor of public policy. “He was one of those rare people who combine towering intelligence with deep compassion, enormous success with an abiding concern for those who didn’t make it.”

Through the years, Williamson also stayed in touch with his Piedmont roots and continued to reach out to others even during his own health struggles.

“Tom was here on January 20 to visit our high school coach and driving instructor Mr. (John “Jack”) Stack, also dying of cancer,” fellow 1964 PHS graduate Christina Orth said. “Ironically, Mr. Stack died on March 2 (at 88), a week later than Tom.”

A native of Plainfield, N.J., born July 14, 1946, Thomas Samuel Williamson Jr. came from a notable family. His father, U.S. Army Lt. Col. Thomas Samuel Williamson Sr., became one of the U.S. military’s first African-American officers to command white troops.

After an assignment in Yokohama, Japan, where the younger Williamson supposedly learned Japanese before he did English, the family settled in Piedmont.

Williamson excelled both academically and athletically at Piedmont High, where he served as student body president and earned letters in football, basketball and track and field. A winner of multiple sports awards — ultimately earning induction into the Piedmont Sports Hall of Fame in 2005 — his gridiron play caught the attention of future Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Bill Walsh, then a Stanford assistant.

Despite a full-ride offer, Williamson accepted an academic scholarship from Harvard, where he continued to earn both academic and athletic honors. An All-Ivy League defensive back, he also headed a black student committee that successfully negotiated with the university’s administration to establish an African-American studies program and to increase enrollment of African-American students.

Graduating magna cum laude in 1968, Williamson was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society and earned a Rhodes Scholarship. Fellow Rhodes Scholars that year included Reich and future President Bill Clinton.

“Together we discovered a world so different from America that it stunned and stirred us,” Reich said in his email. “Tom excelled there, as he did everywhere he went.”

Williamson later spent a year in Ethiopia training U.S. Peace Corps volunteers for an Ethiopian company. Inspired by his work as an advocate with the California Rural Legal Assistance program in the summer of 1967, he then enrolled at Boalt Hall in 1971. Upon graduating, Williamson went to Washington, D.C., to work for Covington and Burling, which permitted young associates to serve six-month rotations with the city’s Neighborhood Legal Services Program.

Williamson twice left the firm for government service, serving as a deputy inspector general for the newly launched Department of Energy under President Jimmy Carter from 1978-1981 and later returning to serve as the chief legal officer, or solicitor, for the Department of Labor under Clinton and Secretary Reich from 1993-1996.

At the DOL, Williamson supervised a staff of some 700, including 500 lawyers.

“He was a trusted and dedicated part of a team that Bill Clinton relied on, and I felt it a privilege to work with Tom,” Reich said.

From the Piedmont Post

(unfortunately there is not a bigger copy available)

Thomas Williamson reflecting in the book - Bill Clinton: The Inside Story by Robert E. Levin, 1992

Williamson began his work as a special adviser to the NFL in 2003. Other highlights of his legal career included leadership of Covington and Burling’s employment practice group, serving on the firm’s management committee and as past president of the D.C. Bar.

Williamson met and befriended numerous colleagues at Covington and Burling, including former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder. He also remained active later in life by participating in several 100-mile bicycle rides.

Williamson’s survivors include his wife of 28 years, Shelley Brazier; children, Thomas S. Williamson III, Taylor Williamson and Christopher Williamson, a daughter from another relationship, Kai Williamson; mother, Winifred Williamson of Piedmont; and sister, Brenda Malone, M.D., an East Bay physician.

Williamson’s father died in 1998. Younger brother George died in 2010, also of cancer. An earlier marriage to Rahel Haile ended in divorce.

A memorial service took place March 16 at the Washington National Cathedral.

“Great guy, great role model,” Orth said.

“He was taken away from us far too soon,” Reich added. “Those of us who knew him and the even larger number who benefited from his work and wisdom will miss him deeply.”

Thomas Williamson with

Bob Meunter (PHS football coach and dear friend of my family)

During high school, Thomas is pictured with the "Kimmer Shielding Fraternity" social club at Piedmont High

Oakland Tribune - Thu - Sep. 2, 1965

Photo of Thomas Williamson at 50th Piedmont High School class of 1964 reunion. Photo posted by Bob Ball (pictured)

THOMAS S. WILLIAMSON JR. | July 14, 1946 - Feb. 24, 2017

U.S. Labor Department solicitor

who helped create Rooney Rule'

By Matt Schudel

The Washington Post

Thomas S. Williamson Jr., a labor and employment lawyer who served as solicitor for the labor Department and helped devise the NFL's "Rooney Rule" to encourage greater diversity in the hiring of coaches, died Feb. 24 at his home in Washington. He was 70.

The cause was pancreatic cancer, said his wife, Shelley Brazier.

Mr. Williamson was a longtime partner and later senior counsel at the Washington law firm of Covington & Burling, where he led the employment practice group. His work included whistleblower and job discrimination cases and negotiating agreements with the Labor Department.

Throughout his career, Mr. Williamson occasionally left the firm for pro bono work, including a year as a staff attorney for the Neighborhood Legal Services Program in 1976. He was deputy inspector general for the U.S. Department of Energy from 1978 to 1981 and, from 1993 to 1996, was the Labor Department's solicitor, or chief legal officer, supervising a staff of 700, including 500

lawyers.

In 2003, when Mr. Williamson was a special adviser to the National Football League, he had a key role in establishing a leaguewide rule encouraging owners to include minority candidates for headcoach openings.

It became known as the Rooney Rule after Dan Rooney, the principal owner of the Steelers and chairman of the owners' diversity committee.

More recently, Mr. Williamson led a legal team defending the same-sex marriage law in the District of Columbia.

He also worked on a nationwide class-action law

suit requiring the U.S. Postal Service to improve American Sign Language interpreter services for its deaf employees.

In 2008, Mr. Williamson was one of two partners at Covington & Burling named by the National Law Journal among "The 50 Most Influential Minority Lawyers in America." The other was Eric H. Holder Jr., who served as U.S. attorney general under President Barack Obama.

Thomas Samuel Williamson Jr. was born July 14, 1946, in Plainfield, N.J. His father, an Army lieutenant colonel, was among the military's first African-American officers placed in command of white troops.

Mr. Williams grew up in Piedmont, Calif. and turned down an athletic scholarship to Stanford University to attend Harvard University, where he was an all-Ivy League defensive back on the football team. One of his teammates

was the actor Tommy Lee Jones. Mr. Williamson graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1968 and was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

He attended the University of Oxford in England on a Rhodes scholarship, then spent a year in Ethiopia training U.S. Peace Corps volunteers for an Ethiopian company.

He was a 1974 graduate of Boalt Hall. the law school of the University of California at Berkelev.

He joined Covington & Burling shortly after graduation and became a partner of the firm in 1982.

Mr. Williamson was a past president of the D.C. Bar and a past co-chair of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

His marriage to Rahel Haile ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife of 28 years. Shellev Brazier of Washington: three children from his second marriage, Thomas S Williamson III, and Taylor Williamson, both of Los

Angeles, and Christopher Williamson of Wausau. Wis.: a daughter from another relationship. Kai Williamson of Atlanta: his mother. Winifred Williamson of Piedmont; and a sister.